x

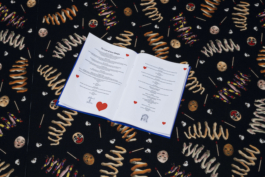

'L'AVANSPETTACOLO'

2020

Group show with Bea Orlandi and Arnaud Wohlhauser

Curated by Olga Generalova, the exhibition stages the proximities of the two artists’ work. The projects on view, made specifically for this occasion, took shape via a regular exchange between Orlandi and Wohlhauser, who had never met before.

L’Avanspettacolo reflects this correspondence. Covering different mediums as well as perspectives, the works on view as well as the artists’ concepts, ideas, and experiences, overlap and intertwine. As separate letters, written or received, everything in it is both head and tail, alternately and reciprocally: the core qualities of each work become solely evident when in dialogue with one another.

The exhibition is named after the “avanspettacolo”, a form of theatrical performance developed in Italy during the fascist era, consisting of short comedic sketches staged before the start of a movie. In Orlandi and Wohlhauser’s work, the promised movie never begins. Instead, the exhibition is set up in 'intervals' - instances marked by objects that act as signifiers of time and in-between states.

'L'AVANSPETTACOLO'

2020

Group show with Arnaud Wohlhauser

Curated by Olga Generalova, the exhibition stages the proximities of the two artists’ work. The projects on view, made specifically for this occasion, took shape via a regular exchange between Orlandi and Wohlhauser, who had never met before.

L’Avanspettacolo reflects this correspondence. Covering different mediums as well as perspectives, the works on view as well as the artists’ concepts, ideas, and experiences, overlap and intertwine. As separate letters, written or received, everything in it is both head and tail, alternately and reciprocally: the core qualities of each work become solely evident when in dialogue with one another.

The exhibition is named after the “avanspettacolo”, a form of theatrical performance developed in Italy during the fascist era, consisting of short comedic sketches staged before the start of a movie. In Orlandi and Wohlhauser’s work, the promised movie never begins. Instead, the exhibition is set up in 'intervals' - instances marked by objects that act as signifiers of time and in-between states.